Information theory in biology

Notes by Liana Merk (2026) and Jenya Belousova (2024)

The Motivation

Way back in lecture 1, we learned that RNA is the intermediary between DNA and protein. The cell transcribes DNA into messenger RNA (mRNA), which is then translated into protein. Not all genes encode for proteins, some genes are transcribed into RNA that can fold into a secondary structure. This structured RNA can perform functions within the cell. The mechanism of translation itself requires two such structured RNA: ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and transfer RNA (tRNA). As we learned in pset1, tRNA reads each codon into an amino acid (more on tRNA in this pset2).

The ribosome is a large complex of RNA and protein. You can think of the bacterial cell more or less as a sack of ribosomes, each one working in overdrive to churn out protein synthesis. The bacterial cell often encodes more than one copy of ribosomal RNA within its genome (E. coli has seven). Ribosomal RNA changes so infrequently during the course of evolution that it is often used as a phylogenetic marker to trace the relatedness between species.

Example of E. coli small subunit rRNA showing primary sequence schematic (left), secondary structure (from Petrov et al., and 3D structure (RNA only shown, from PDB 6AWB).

The RNA world hypothesis (that the first information storage and catalytic molecules were RNA) is supported by the fact that replication's core machinery is composed primarily of RNA. The ribosome is not a protein machine that just happens to include RNA! Ribosomal rRNA serves as both the physical scaffold and is the catalyst actually forming the peptide bonds. Other types of catalytic RNAs, called "ribozymes", exist across the tree of life. Even larger classes of structured RNA exist and efforts from the field to compile these have resulted in a curated dataset, Rfam

In structured RNA, selection frequently acts more on the base paired structure rather than the individual nucleotides. Notice how this is different from protein sequences, where given amino acid properties (hydrophobicity, steric hinderance, and electrostatics) must be conserved to maintain function. You can get a lot of signal about base pairing by looking at multiple sequence alignments (MSA). By looking at each pair of columns, you can determine which positions change together across evolution. We call this "covariation", and the calculation we can use to pull this out is called Mutual Information.

Mutual information calculation

From lecture, let's pull up mutual information:

Where \(i, j\) are columns of the MSA, \(p_i(a)\) is the probability of nucleotide \(a\) in column \(i\), and \(p_{ij}(a, b)\) is the joint probability of seeing \(a\) in column \(i\) and \(b\) in column \(j\). We take the maximum likelihood estimation of these probabilities to be the frequency within the MSA.

Here is the toy example of its application:

In this toy example we have a lot of cases where we cannot compute the logarithm because of 0 probability. We show one example of this (T-A), but we would need to account for this for any pairs not present in the MSA. In actual alignments these cases will be much less common because we would have more sequences.

One way to deal with this uncertainty is to treat \(\log_2 \frac{p_{ij}(a,b)}{p_i(a) p_j(b)}= 0\) for a pair that doesn't exist in the MSA, such that we don't need to actually calculate log 0.

Mutual information distribution: actual and randomized

After your python function has computed \(M_{ij}\) for each pair of columns, you get a distribution of 2556 \(M_{ij}\) values for the actual alignment. Pset requires to plot this distribution, so let us show it schematically (assuming we don't know yet how it actually will look like):

To obtain negative control we can perform a shuffling procedure and plot a fake \(M_{ij}\) distribution. Survival function might help to justify your choice of a "significant" \(M_{ij}\) threshold, so it is also required to be plotted.

Other applications of mutual information

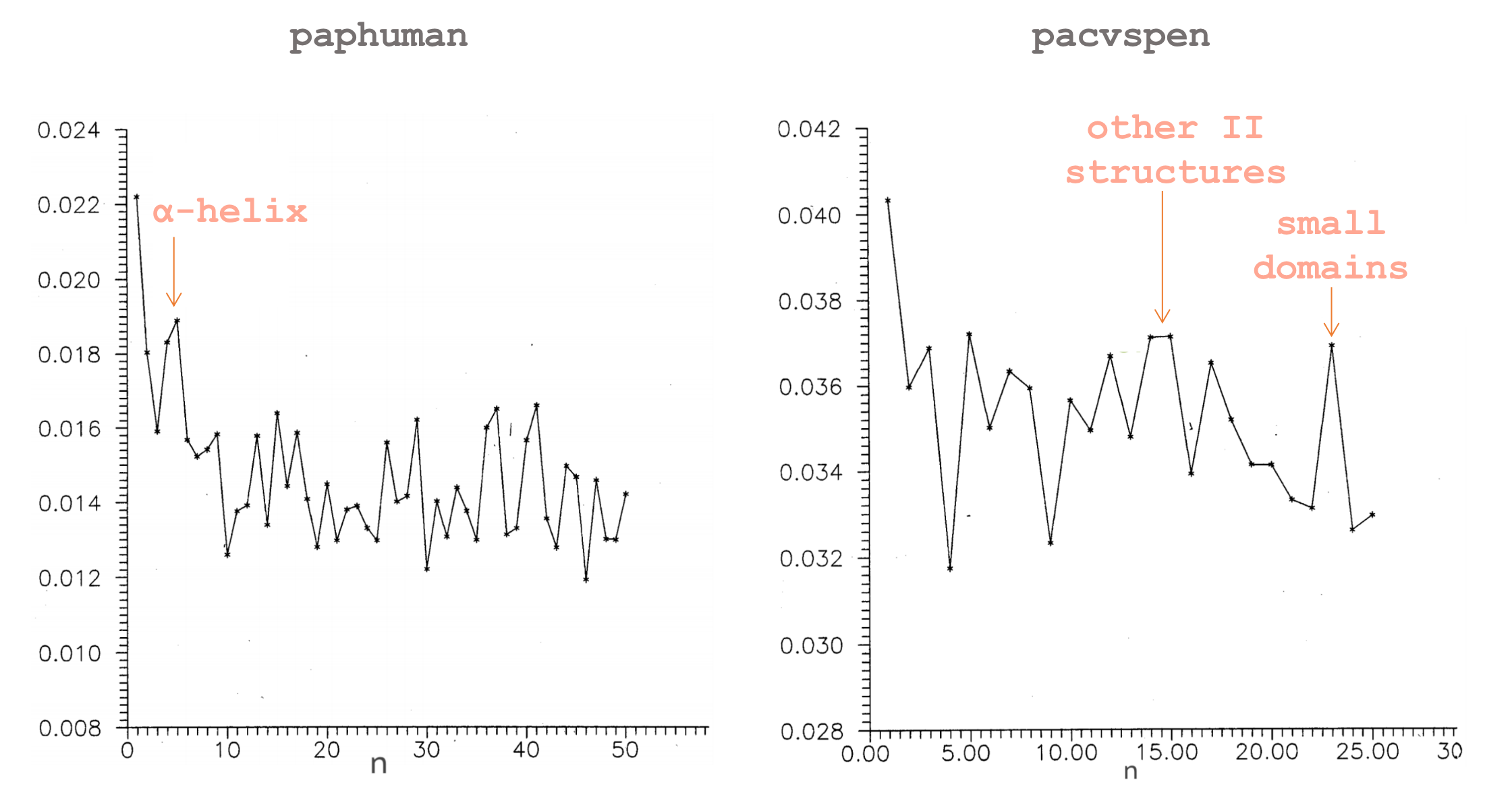

Sometimes we are interested not in specific values of mutual information for particular positions of MSA, but rather more broadly in distribution of dependencies within a biomolecule. Another use of mutual information metric is to plot how it depends on the distance between monomers (\(n\)) in general. The authors in the work Ebeling & Frommel, 1998 performed such analysis for two proteins.

Paphuman has a well-pronounced peak around \(n=4\). Indeed, apolipoproteins are \(\alpha\)-helix enriched and in \(\alpha\)-helices approximately every fourth amino acid interact with each other. Multifunctional enzyme pacsven has peaks around \(n=15\) and \(n=25\), which are the size of secondary structural elements and small domains, respectively.

This analysis allows us to draw some conclusions about protein 3D structure and, in some cases, even function by just looking at its sequence, which is quite impressive.

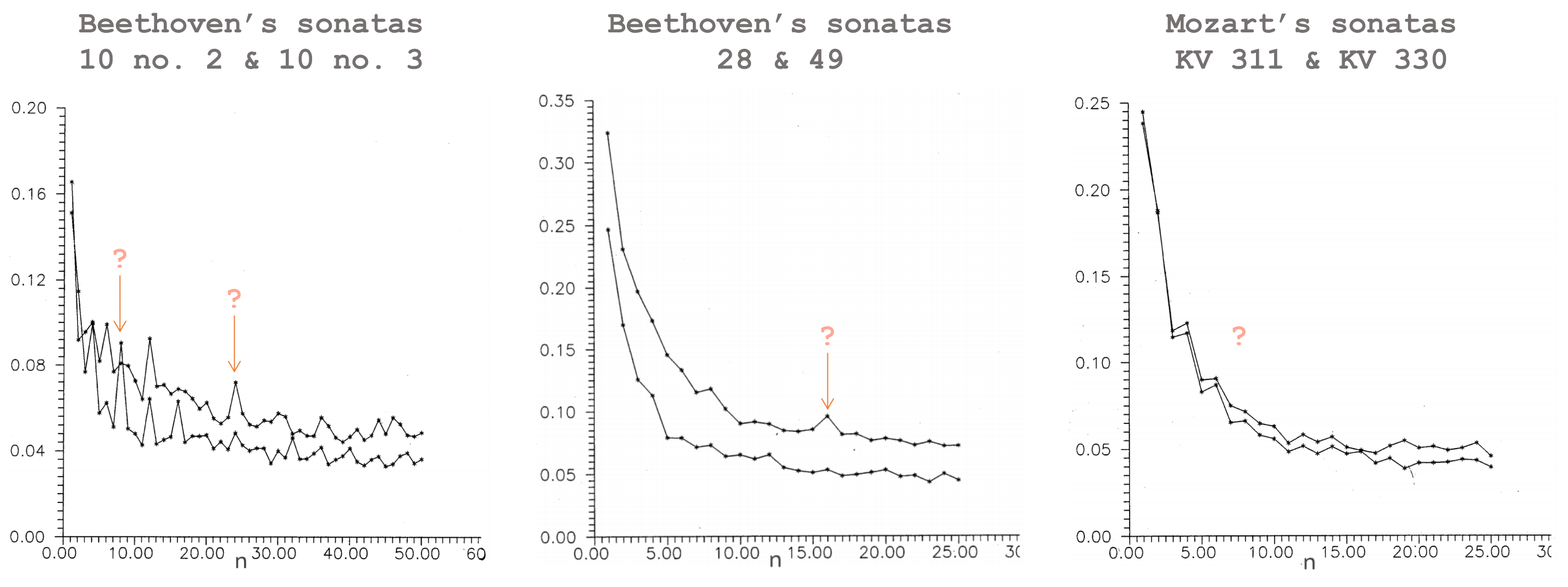

To the large extent we are surrounded by the world of evolving sequences, and not only biological. Same authors repeat this analysis for music written by different composers.

Since music mostly has an effect on the brain, it is hard to talk about any musical "phenotype" at the current state of development of neural sciences. But music is definitely well-structured and these plots might be a good way to capture these structures, even though we don't know how to describe them (yet).

Numpy and Matplotlib practice notebook

Download a numpy/matplotlib practice Jupyter notebook from here.